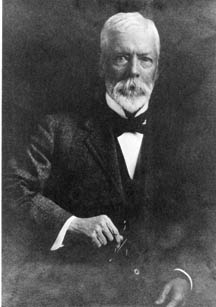

Thomas Lamb Eliot

I got a card from a roomful of people the other day. You, know, everyone signs it and some of them know you well, some not at all. Some of them love you and some of them are kinda glad to see the back of you. Still I love getting those cards. I read them, hoping to find something interesting, some insight into how others see me. One sentiment was from a friend who is as busy as Thomas Lamb Eliot was (see previous post). She wrote "thanks for all you do." I fell that tiny little stab of disappointment when a compliment misses the mark.

Yet I know I have written that on people's cards under similar circumstances. I wrote it as a compliment and a way of saying, 'I noticed how much you do.' One of the things that happens in the world of do-gooding and community engagement is no one usually DOES notice. So I have given it out as a compliment. But, no more.

If you are someone who obsessively does things, then you don't need to be encouraged in your mild derangement. If you aren't, you do it as an expression of who you are, then you would like to have your shining self noticed once in a while. Next time, I am going to say 'thank you for your wonderful self.' or 'I love your wisdom and understanding.' or even ' I am going to miss your beautiful smile."

TLE wrote the above words at his retirement celebration after a lifetime of being celebrated for all he did. He did a lot, but he had come to see that the doing was not what it was about. He was a mature minister formed in the fires of his work and when it was all done, he was more then that work, and he knew it.

Blessings on what we are.